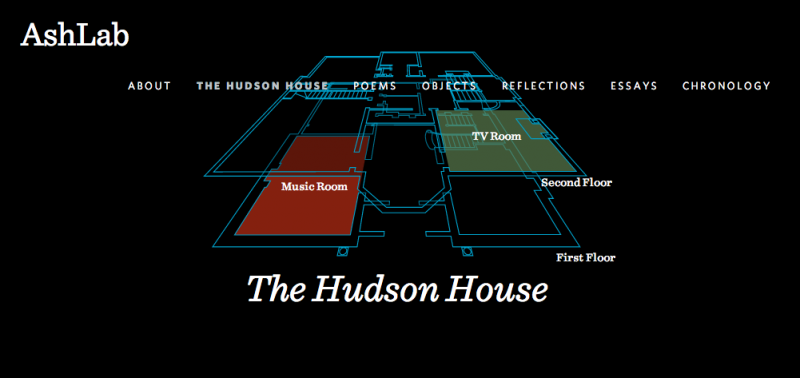

In 2012, a group of faculty, staff and students at The New School for Social Research in New York began to document two rooms, the Music Room and the TV Room, in John Ashbery’s home in Hudson, New York. The resultant project, AshLab, seeks to catalog and reproduce the Hudson house and its contents online. Ashbery bought his Victorian townhouse in 1978. Around 1984, Ashbery and his partner David Kermani set about restoring and renovating the house, filling it with objects and artworks they collected, as well as other furniture and personal items. Ashbery and Kermani still live in the house, but the producers of AshLab approached the house much like curators of a historic house museum. The digital representations of the Hudson house are pristine. The objects remain, in the website’s 360-degree digital views, frozen.

Ultimately, it’s not really the images of private spaces that make AshLab so compelling. In some ways, the access granted to a viewer of AshLab isn’t much more open than most house museums. The importance of AshLab, its contribution to the representation of artists’ homes as sites of study, lies in the work that AshLab students and scholars did to bring Ashbery’s presence into the spaces. To click on a lamp, which by all appearances is nothing valuable or rare, and to hear a sound recording of Ashbery explaining that he bought it while traveling in Paris as a young man on a Fulbright fellowship … this is where the staid décor of house museums becomes something more. We gain access to how Ashbery lived with his objects. Each object carries with it a history unique to it based on the way its owner used it.

It’s rare that the site of an archive is also that archive’s source. As Ann Cvetkovich observed in her writing on archives, institutions can often inject a feeling of preciousness into people’s personal effects. Admitted into collections and divorced from their original context, clues to their use or meaning to the owner are difficult to trace. Ironically, sometimes having items in an institutional repository (Cvetkovich cites Gertrude Stein’s hand towels, eyeglasses, stationery) can imbue them with more meaning than perhaps they may have had simply laying around somebody’s house. As exciting as it is to designate a fabric-covered button in Stein’s collection as a “tender button,” it is also important to remember that some items were there just because they were necessary. Kermani recalls that a lamp in Ashbery’s collection was acquired “because he needed a lamp.” This doesn’t negate the value of the house’s other lamps, but it does offer more information than an institutional archive usually does.

Adam Fitzgerald, a poet and professor at the New School and one of the organizers of AshLab, discussed some of the issues that arose as they had to make choices about what to present in the house, and how to present it. -- Chelsea Weathers

Can you describe briefly the initial conception and history of AshLab? How did this project get started?

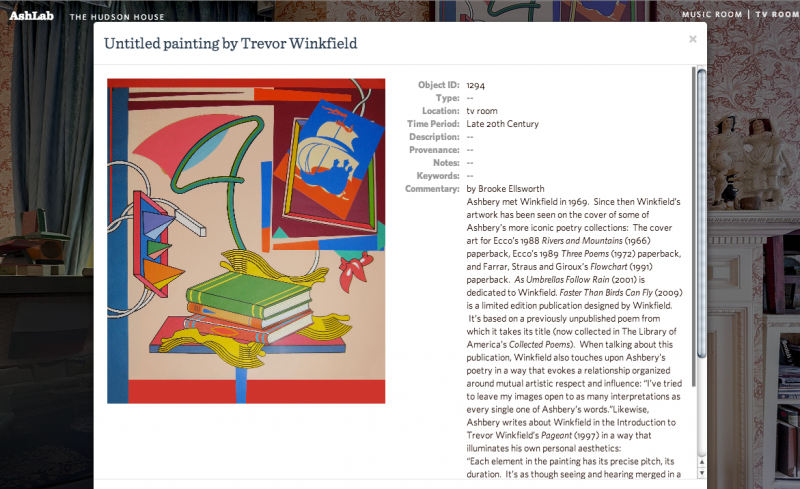

AshLab began with conversations between David Kermani and Robert Polito, then Director of The New School’s graduate writing program. David, who has long devoted himself to helping preserve and document Ashbery’s bibliographic archives, has in recent years given unprecedented access to emerging and renowned scholars seeking to understand Ashbery’s personal spaces, his domestic archive, in fact. I think the question that arose was how best to preserve the Hudson house, which is a post-Victorian home that Ashbery has made a living collage out of for nearly thirty years. Robert’s sense, from what I understand (I came in later to the project), was why not start by having New School students document and write about the treasure trove of Ashbery’s art collections, furnishings, antiques, knickknacks, bric-a-brac, weirdo things like aquarium figurines. As the project moved forward, Tom Healy and myself joined in, as did Irwin Chin, a professor of information design at Parsons. New School’s various divisions and schools aren’t known for collaborating often—so this course, from the start, taught by four different faculty members, was a huge risk and experiment. Brooke Ellsworth, who was a student the first semester and stayed on, quickly rose to being a TA and then part of the faculty team—she was invaluable throughout. That’s one of the most unique things I can imagine happening in a long-term collaborative course like ours was.

All the rooms in Ashbery’s Hudson House seem very meticulously arranged. How did Ashbery, or even the AshLab group, go about preparing his rooms to be cataloged and photographed? Is there much of a contrast between how they appear as spaces of everyday living and how they appear on AshLab?

AshLab focused its first semester on a single room, the Music Room, or so it was called in the architect’s designs. From the start, John kept a piano in there, which he found around Hudson, and had in working order while a friend and pianist watched the house and noodled on the keys. In the second semester, we focused on the TV room, where John spends much of his time while in Hudson, mostly watching Turner Classic Movies, as well as the news channels, local and national. He’s addicted!

As for preparing the rooms, we didn’t do much. We wanted to see them as they had developed … and continue! Irwin brought in a team of high-grade professional 360 panorama photographers. They were able to realize these rooms in startling accuracy, and present something in a digital format we could only dream about—that is, not just isolated stills or shots of this or that combination, or sequence of objects, but an illusory seamlessness that lets viewers believe they’re right there in Ashbery’s living spaces, seeing his wacky and lovely environments on their own. When the photographers came, I’m sure some of the daily detritus of newspapers and personal ephemera was cleared away—these are, after all, living spaces, private, personal. So we had to negotiate that tension: in one sense, John has created a theater-set for his imagination, full of ventriloquy and quotation just like his poetry. In another sense, he’s just trying to do what we all do at home, and who wants that broadcast, let alone documented for eternity?

What kind of instruction did the grad students receive in terms of their descriptions of the items?

Students were given a tremendous amount of support and private access to materials from the Ashbery Resource Center, an organization based in Hudson that I myself once worked for from 2006-2007, as a rather sluggish but mostly enthused intern. It didn’t quite dawn on me at the time, that years later, I would have completed an MFA degree and be teaching these spaces, in connection to John’s work and much else in contemporary culture, years later. Tim O’Connor, David Kermani, John himself on class visits to Hudson, were all enormously helpful with letting students make use of existing research, as well as expand their descriptions with original research, through a host of factors: interviews, Googling, and even just asking unanswerable questions. One of the ongoing challenges was which tone to strike for the course, and that included how to document and describe objects. While we wanted the credibility of a museum, none of us, instructors included, were trained or professional archivists or curatorial specialists. We figured that since the class was offered through the Writing Program, and featured Media Lab students from Parsons, as well as Riggio undergrad honors students, why not let things oscillate and detour, as I think the best essays do—but even there, there was range. Things became creative, personal, eccentric, and we did our best to encourage that even as we dreamed of standards and our project’s future audience.

Some of the items in the house with cataloging information are also linked to poems. How did that happen?

This is really owing to two people. First, Robert Polito who helped formulate conceptually what we were up to. As he has said, AshLab is about three houses: an actual, literal house in Hudson that John Ashbery lives in; a metaphorical, physical house that includes all of Ashbery’s creative work, foremost his majestic poems; and finally, a digital house, or AshLab, that allows for points of entry, or roots to link and re-trace connections, possibilities, similarities, anecdotal or historical memory-webbing. Second, Irwin Chen, who could supply the technological savvy and vision to really make the website interface a reality. Anyone who knows web design knows there’s a back end and a front end, basically the difference between coding and the user experience. Without his genius for thinking outside the box but also having gracefulness and lucidity as a designer, we wouldn’t really have been able to share what we were learning, sharing and collecting.

One thing that I find so interesting about the site is that it in some ways offers more intimate access to objects and spaces than tours of historic homes that happen in real life do. What are your goals for how visitors to AshLab will engage with the site?

I’m not sure what our goals were! In truth, we had many goals, but they changed over the course of the five semesters, as we had to shrink back some of the project’s plenitudinous plenty and focus more intensely on things that remained elusive but crucial. I can’t speak for anyone else, but I think it would be great if this project, AshLab as a website for readers and scholars of Ashbery’s work, could give them a visual, textual—finally, an interactive—demonstration of one writer embracing his bounty of inspirations, from objects to words.

What was the most difficult part about this project?

I think the most difficult part of this project is akin to the difficulty of John’s work: there is so much of it, and even within a single poem, a single line—there can be a gaping abyss of allusion, reference, appropriation, learning, etc. It can be daunting. It’s one thing to imagine a human being, a poet and artist, in John’s case, channeling and coalescing his erudition and polyglot polymath knowledges, but how as a teacher, as a student, does one parse it out, learn it well enough to recognize it and say something helpful among the busy, distracted beauty of it all? Luckily, we never had the arrogance to think anything we were after was completist, definitive, or the final statement. It’s really an invitation to consider, well, everything. One of John’s phrases comes back to me: a “hymn to possibility.”

All images come from AshLab's interactive website, and are reproduced with permission.

* * *

Adam Fitzgerald is a poet who teaches creative writing and literature at Rutgers University, The New School and New York University. He is the author of The Late Parade, his debut collection of poems from W.W. Norton’s Liveright imprint. He is the founding editor of the poetry journal Maggy and contributing editor for The American Reader.